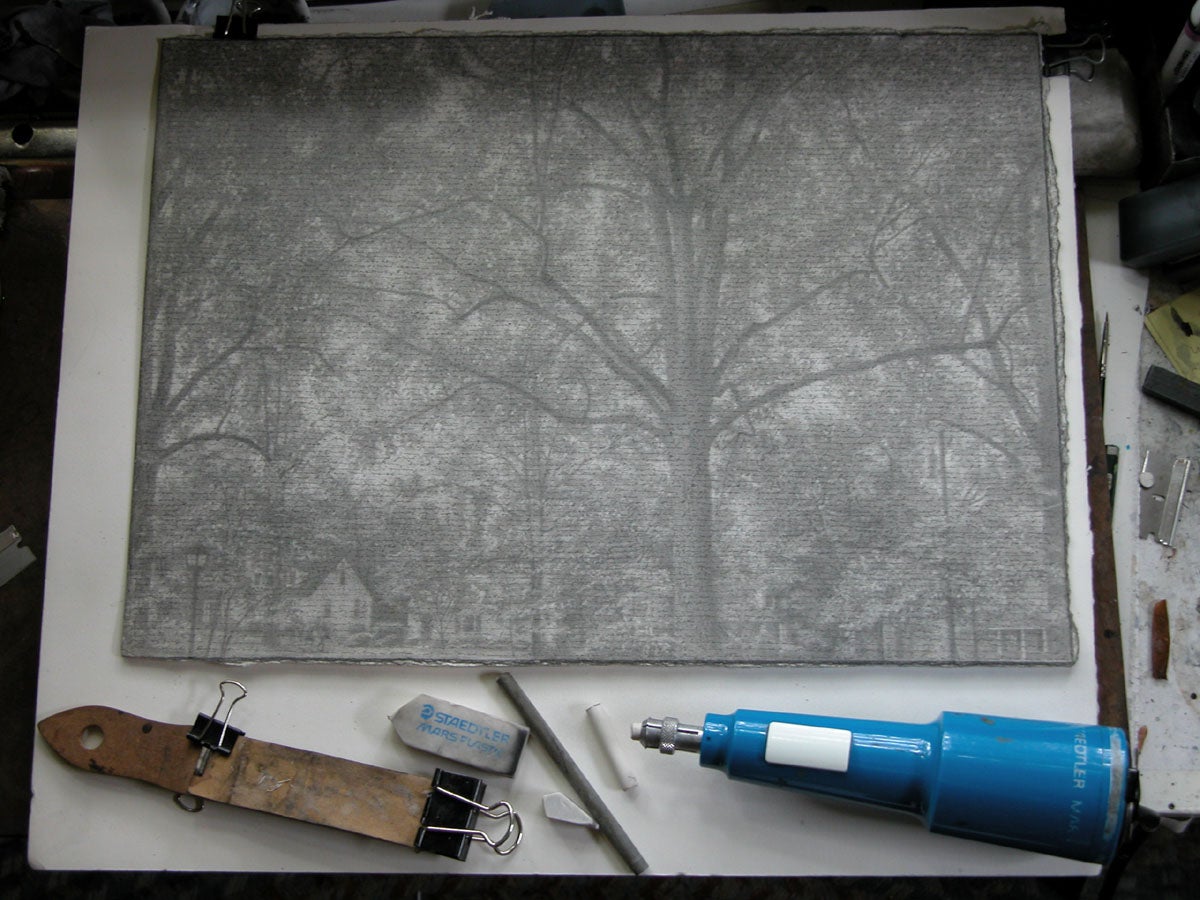

(above): Spring Twilight, graphite on Fabriano paper, (work in progress) with (from left) sanding block, plastic eraser with cut fragment, hard gray grinding eraser, white plastic eraser refill and electric eraser.

Erasing

In the early 1950’s, upstart artist Robert Rauschenberg arrived at the door of one of the preeminent figures in painting at the time, Willem de Kooning. Rauschenberg went with the idea of asking DeKooning for a drawing, not to acquire but one to erase. de Kooning, a bit wary, decided to go along, and came forward with a heavily worked sheet; a drawing that was going to be hard to obliterate, and one he was going to miss. The younger artist spent about a month and myriad erasers of all kinds taking the crayon, grease pencil, ink, and graphite drawing back to white paper, leaving only a ghost of the original image. Rauschenberg framed the drawing and labeled it with the title: Erased de Kooning Drawing.

There are many things to which I respond in Rauschenberg’s action; but what consistently resounds is that Rauschenberg took the concept of erasing to its positive limit: erasing can be a creative force, a tool for making and not just for eliminating. While I’ve come to view erasers from that perspective, in my youth I believed that erasers save us from mistakes. In drawing classes I heard the teacher say, use the eraser as much as the pencil, but it took me years to unplug from the attitude I was fixing my drawing.

In recent years, working in graphite with greater frequency has helped me cultivate a broader, more sophisticated use of the eraser. In the studio I use plastic erasers almost all the time. The Staedtler Mars Plastic works beautifully for my purposes and I often cut the eraser into small chunks shaping it to specific cleanup areas. I also keep a clean sanding board nearby while I’m working; sanding the residue media off of the eraser can help insure a clean erasure. Allowing the eraser to stay dirty will allow another effect; media collected on the eraser can cause a desirable smearing across a drawing’s surface and suffuse the drawing with atmosphere. (see online journal entry, Graphite)

One of my favorite tools is the electric eraser (see images below and above), a device that certainly would have helped speed Rauschenberg’s project along. Developed for architects, a pencil-sized cylinder of eraser is fitted into a tube-like spinning chamber, allowing an artist to focus the location and pressure of erasing to an amazing degree. I commonly use the plastic eraser point, but a grittier hard eraser is available that can actually grind away extremely potent marks from the paper’s surface if executed carefully; even dry watercolor can be whisked away if just the right amount of pressure is used in quick bursts. But care must be used with the grittier eraser; sustained pressure can result in an overly-abraded paper surface that can never be repaired. Also note that the gray color of the grittier eraser can penetrate and leave a stain if not used judiciously.

The electric eraser has become integral to the development of one of my current drawings; a piece I began in 2005. I’m constructing the image entitled Spring Twilight in 2B mechanical pencil. Limiting my use this weight pencil is helping me refrain from obliterating fine ink writing that underpins the entire drawing. But the pitfall is that employing uniform weight graphite throughout tends towards formlessness; using the focused point of the electric eraser is a good way to pull highlights out, as well as carve out stronger shapes. Working back and forth between the sharp graphite tip of the mechanical pencil and the crisp electric eraser has helped me build a complex drawing surface. Pencil and eraser are equal partners as tools of drawing.

One other point comes to mind; I believe it was Rauschenberg’s teacher Josef Albers that taught the younger artist, “Contrast creates interest”. This motto has been a particularly useful for me over the years; I have interpreted this statement to mean that the stronger the contrast between elements of value, color, or line in any area of a work of art, the more the area will tend to detain the eye. A work of art can become a hierarchy of points of visual interest. Learning how to move the eye through the work of art can be a delicate dance; especially when approaching a complex subject like the galaxy of leaves outside my window. My intention in Spring Twilight is to keep the eye moving through an intricate field of elements; thus it makes sense to restrict the drawing to a middle gray 2B pencil shepherded by electric eraser. A darker pencil might invite too much contrast; arresting the eye and subverting multitudes of forms offered in the visual field.

(above) The artist drawing with the electric eraser.