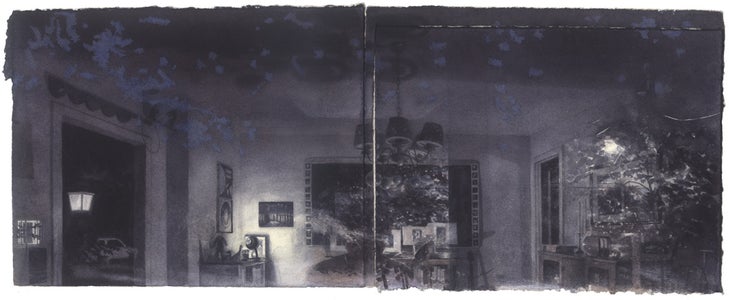

Self-Portait with Night: Pieced Panels I 2009 watercolor, gouache, graphite, and pen and ink on Fabriano paper 5 5/8 x 14 1/4"

Conversation with the Artist in his Studio

This conversation between Charles Ritchie and Richard Waller took place in the artist's studio in Silver Spring, Maryland, on Saturday, November 21, 1992, and has been edited.

How did you come to the American home and suburbia as your central subject matter?

I love the American landscape, the home and its history, and particularly our suburban architecture. I like the American sense of space, the yard, and the netherlands that grow up between houses. I came to all of this from growing up in the suburbs; to paraphrase Mark Twain, "paint what you know," and I know suburbia well. As a child, I moved with my family every two or three years, and the houses and landscape became my emotional sounding board. The solitude represented in these houses is symbolic for everyone and certainly myself.

The exhibition is subtitled "the interior landscape." How does this refer to that metaphor?

The landscape is a symbol for the outer world, the desire to engage in the world. The interior is the self and the desire to be secure and protected within the home. The phrase merges the two aspects.

And Emily Dickinson's poem I dwell in Possibility is central to these thoughts?

The self becomes the house, and the house is possibility, responding to the world as it happens. Dickinson's house involves both the world without and within her "Paradise." Roof and sky are interchangeable, open and closed in the same breath. The chambers, as cedars, are permeable but difficult to see through. There is an implication of moving within the space of the self. I use this imagery, particularly in the reflection pieces where interior moves out and exterior moves in.

Your journals are crucial to an understanding of your imagery and the works in the exhibition.

The idea for keeping things in book form goes back to my childhood. In grade school I made books depicting imaginary worlds. In high school I drew, wrote, and composed songs in notebooks. By 1977 I had begun my present series, which now numbers more than eighty. These books contain dream imagery and narratives, directions to a new piece or old pieces, quotations, or just things I am thinking. They are evolving into a daily sketchbook to record ideas that strike me as significant. The journals are very private. The handwriting is generally illegible to other people, a small notehand I developed to get ideas down quickly.

The journals, then, are undeniably an integral aspect of your work. What is your process?

My first step is walking around the house, passing my subjects a thousand times. Suddenly, I know "that's it," an object seen in a particular light in the atmosphere of a particular day. The idea goes into the journal. My first images are very abstract, starting only in terms of the arrangements of forms and depiction in a loose sense. When I have decided what the image will be, I think about what paper to use. Paper is a wonderfully versatile support; I can easily adjust the size and shape in relation to the image. I keep lots of pieces of paper around the house as well as work tables with watercolor. Michelangelo's seeing the subject in the stone is analogous to my seeing the image in the paper. When I have determined and adjusted the paper, a few lines of pencil establish the composition. Often I will then do studies. Adding the tones in watercolor, I refine the image with pen and ink that has been diluted to various weights. I don't add white highlights but save the white of the paper to illuminate the work. I build up an image, and the creative process goes back and forth.

Although the largest drawing in the exhibition is only 29 inches wide, this seems very large because most of your pieces are extremely small in scale.

Small scale has a lot to do with being able to see the image all at once. I love my world transferred into this intimate universe I'm creating.

When we look at your work, we see a world of tonalities with very little color.

My perception of the suburban world is subdued, but I do select. I focus on the mystery of the contrast of dark and light. Night is a favorite theme because it filters out so much. It reduces things, levels things out, creates a powerful negative space. I am fascinated by empty spaces and the spirit of things.

A wonderful African proverb, "all cats are black at night," captures perfectly that filtering of detail. From watching people look at your work, I see they are drawn into your universe. The photographic quality might be the initial seduction.

By being seductive, I can deal with more difficult issues. The threatening feeling of discomfort and fear in these spaces keeps my work from just depicting a space. You are thrust inside with your own solitude. There is a lot more about surface, texture, accidental invention, and an awareness of the world's details that goes beyond the camera.

The exhibition includes interior, exterior, and reflection pieces. One hundred feet in any direction from your studio encompasses your depicted world.

My pieces are about the house and its objects and environs, but also about the time of day. From before daybreak through mid-morning, I sit and work in front of windows watching the transition from dark to light. Time causes movement from inside to outside and where they meet in reflection.

The window, a major recurring theme, seems to be important both as physical fact and as metaphor.

It is the picture plane, the Renaissance illusory window into the different space of the work of art. The window is the meeting point of the world outside and the security of the home.

Margritte's windows are symbolic of the illusion of what we see out of the window. Your work also seems to play with what is being revealed or concealed.

That disorientation is part of what I want. You are not quite sure where you stand and it makes you uncomfortable. The grid of panes breaks up the image further. The mullions even aggressively fragment my own image in one of the self-portraits.

Interior/Exterior is the most confusing in terms of the viewer figuring out what is what, what is reflection, what is going on. Is this unease, also seen in "Burning," a statement about suburban life?

No, but it is a critique of my own life and world, of things I'm uncomfortable with in my life. I do love suburbia and the things I'm around. There is no satire. I want to look at the pleasure of my world and express the joys but also the great emptiness. The image of my guitar shows pleasure, but the case implies coffin-like containment. Other recurring objects are the chair, other household objects, the two houses across the street. They are all symbols, in essence self-portraits. I find my emotions, my discomfort and pleasure in these objects. The two houses could even be seen as my wife and myself. Looking back, I see private events in my life.

Some part remains the artist's story, but your works resonate with familiarity for us. For example, Foundation represents a traumatic change.

My house had an empty back lot with tulip poplars. It was symbolic for me of the woods. My studio windows overlook this space. They removed the trees and poured the house's foundation, a gaping wound in my landscape. Later the house blocked the view of the valley beyond. This is a loss I have to accept, and yet it represents new possibilities. Morandi repeatedly painted a group of objects with very slight changes. He was dealing with various internal states, and he projected not only his own experience but the universe upon those objects.

In addition to Morandi, what other artists have influenced your thinking and work?

Velazquez comes to my mind for his self-scrutiny and scrutiny of his surroundings in the play of reflection and implied outside space. And I think of Vermeer and his light, and Rembrandt's night pieces. Claude Lorraine's landscapes have the atmosphere that envelops everything. I admire Edward Hopper for his direct approach to the American landscape. Leonardo's notebooks and his scientific approach to observation is something I try to emulate in my journals, and also Delacroix and his North African journals that reduce his vision down to an intimate world. Titian's "Sacred and Profane Love" is one of my favorite paintings. Magritte's subtle humor is similar to what I find in the objects I portray.

Magritte's ability to make us look again at the familiar is also in your work. As in Norman Bryson's essays on still life, you too are asking us look at the overlooked. For example, we overlook, indeed learn to overlook, reflections in windows.

You have to ignore the reflection to understand your place in space. I'm interested in bringing these reflections back to our vision. I want to observe them, to see this floating window among tree limbs. To see them as disturbing, beautiful, and strange.

And magical you solidify something that is truly changeable and ephemeral.

The effect is very short-lived, and the image is a compilation of many events. It is a cinematic distillation of the moment. I am very interested in film because it happens in time. It's that rectangular illusory window happening in time.

You bring together two aspects, an expressionistic approach with a tight hyper-realism, which seems to heighten the impact of your pictorial realism.

I do it to make it new again. I want a dream-like window into a very enticing space, but also I emphasize the reality of the process and the end of the illusion at the paper's edge. The expressiveness sets the stage for the drama to occur.

In Interior with Still Life the space is atmospheric, even mystical. For me, seeing the real space here in your studio demonstrates your sensitive selectivity.

The imagination of the viewer will insert elements that are needed. The long format plays on the cinematic movement as you move through it. The intimate space you crawl inside, alone with your own responses to what is in the space.

Viewing the exhibition, we feel a certain security. We never step outside of your house. We may look out of the window, but we do not leave your house. This gives us an overwhelming sense of being in this particular place, of experiencing your world.

Is it really secure? It is both secure and insecure. The house is a symbol of what is secure, I am drawing the object of desire. My art makes me ask questions, and I hope it makes others ask questions. There's much more here than we let ourselves to see, more that what we assume is here. I am commenting on my world and myself. There are many conversations going on between the drawings in the exhibition.

This conversation relates to the 1993 exhibition Charles Ritchie: The Interior Landscape, a traveling exhibition coorganized by the University of Richmond and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The text is copyrighted and is used by permission.