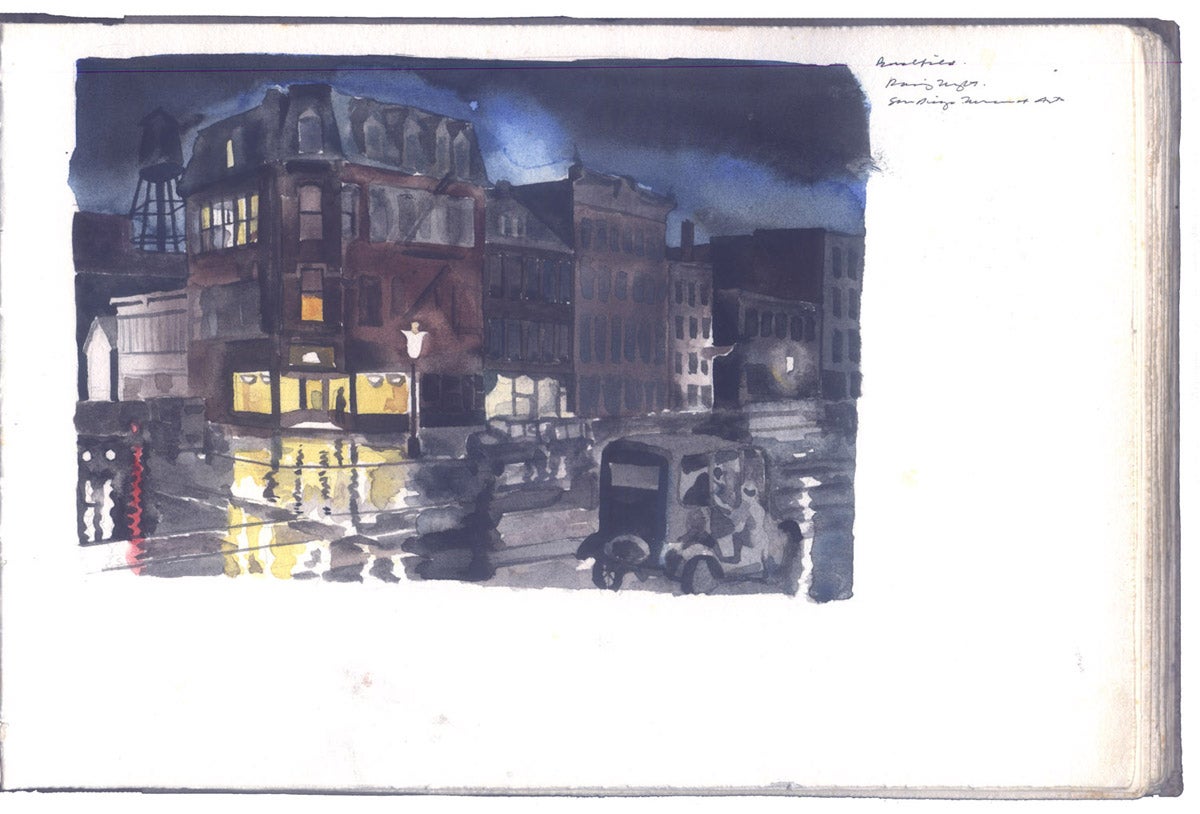

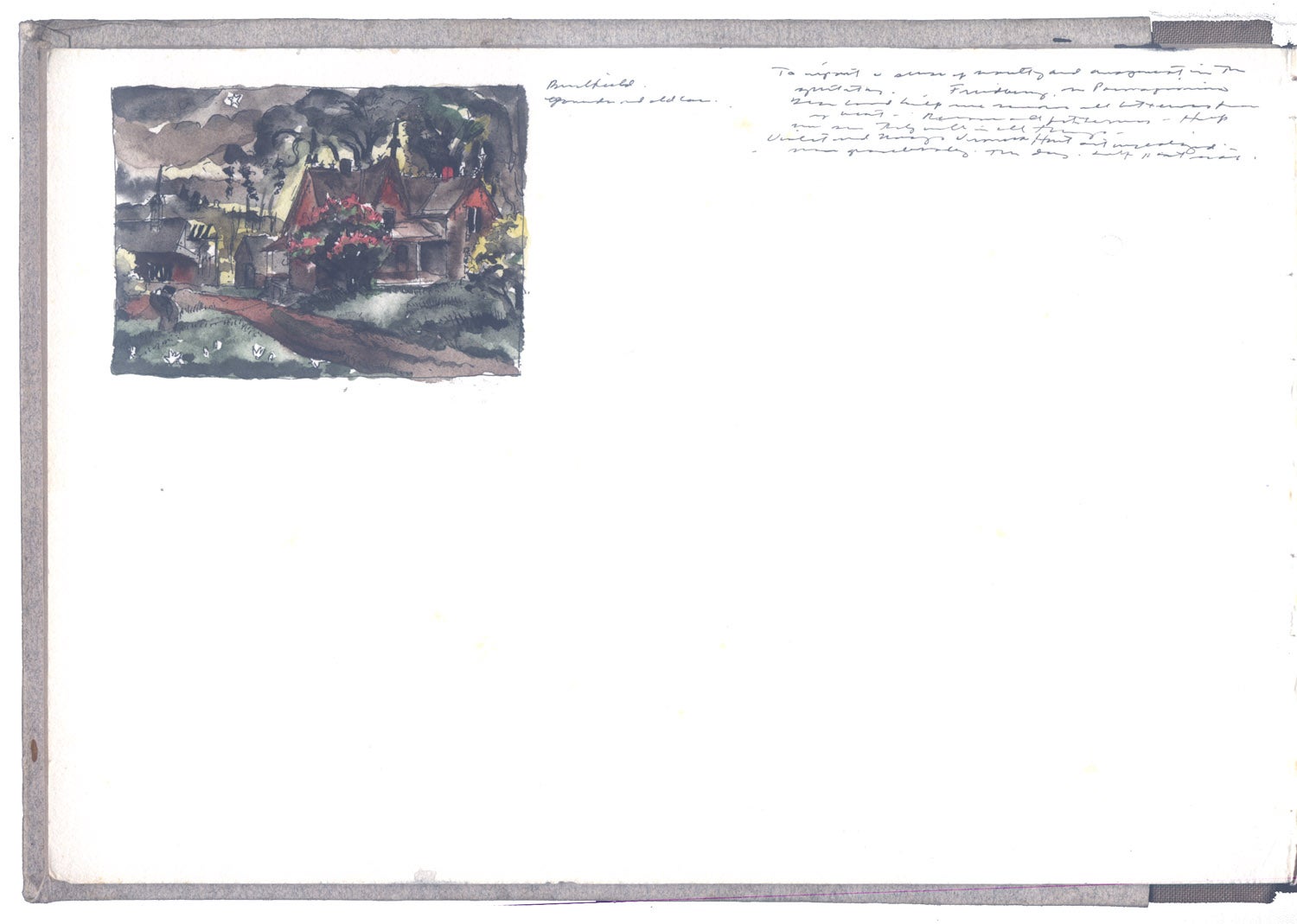

(Top and below) Charles Ritchie after a watercolor by Charles Burchfield, from an uncatalogued sketchbook, 1986, page size: 6 x 9', watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink on wove paper

Charles Burchfield is an artist I have uncovered slowly over the years. I first encountered his art while I was in my early 20s, just after undergraduate school. I discovered him in an out-of-print catalogue by Matthew Baigell (Charles Burchfield, Watson-Guptill, 1976); the book was remaindered and I bought it for a song. I still look at that book. One of my best buys ever. I've always been attracted to Burchfield's palette; those earthy, tones of the natural world. Burchfield's adeptness with line and his fearlessness with black also entranced me. I found a kindred spirit in the artist's love of using paper as a support. In truth, I personally prefer Burchfield's handling of watercolor on paper to his oil paintings on canvas. In my mind, the oils lack the vitality of his watercolors. But I tend to prefer works on paper, so I may just be showing my bias.

A friend recently used the term 'farmer of images' and I think it's an appropriate term for Burchfield in that his art is so tuned to the seasons, weather, and times of day. I also loved the way Burchfield added sheets of paper to extend compositions. His idea of reworking and reforming earlier compositions seems so powerful to me; stretching the development of a watercolor across decades. It demonstrates that a work of art can include the evidence of an artist's growth over a lifetime. I think Burchfield's works have influenced me in all the things I've mentioned above. But I can't say that I've adapted any major element of Burchfield's vocabulary; for example, I certainly can't say that I have his love of dreaming up forms that carry a specific personal meaning; the artist invented forms that were supposed to evoke particular emotional states. However, Burchfield's rhapsodizing on the American landscape and interior is certainly an enthusiasm of mine.

Much later in life I learned that Burchfield kept a journal, when I discovered a book by J. Benjamin Townsend (Charles Burchfield's Journals: The Poetry of Place, 1993, State University of New York Press.) I can't say that I've read many of the artist's journal entries to this point, just enough to get a feel for his writing. The entries I've seen record daily events, natural phenomena, and recount the artist's emotional states. When I recently learned how many journals Burchfield actually kept over his lifetime I was floored; sixty-seven books containing around 10,000 pages. And I was very interested to discover that he tended to make the notebooks himself, in a wonderful informal way; paper folded and sewn together so simply. While all of this does have a connection to what I do, there is no way I can say that Burchfield's journals have influenced me. My journals began as sketchbooks and the image component has been the essential element. I have not seen any of Burchfield's journals that could be called sketchbooks although I understand there are occasional sketches and doodles in some of the journals. Burchfield also collaged and inserted pages at times, something I never do. I'm sure Burchfield tracked his dreams to some degree, but that is certainly not the focus of his journaling. Dreams are, of course, the core of my project as I use them to plumb my psychological depths, attempting to read the symbols. And I never try to consciously project these symbols into my art.

What I can say most attracted me to Burchfield was the way his pictures made the everyday world come alive; he charts the mystery that is all around him. And I find it in his work of every period, discovering the magic in the mundane no matter what style he employs. Many of the discussions I have read over the years regard Burchfield's middle period of work less important than his early work and late work. There is a tendency is to glorify the early modernist period where his forms were more invented and less traditionally depictive. Burchfield recovered his improvisational early language for his later work, and that work has been championed too. However, I've imagined that Burchfield was like Picasso. After a period of radical invention he needed to revisit a more traditional structure. Picasso, of course turned back to Classicism after stirring the avant-garde movement of Cubism. As for me, I am attracted to Picasso's classicism perhaps even more than his Cubist works.

Sincere thanks to artist and friend Emilie Keim who sparked this discussion about Charles Burchfield. You can see Emilie's art here.

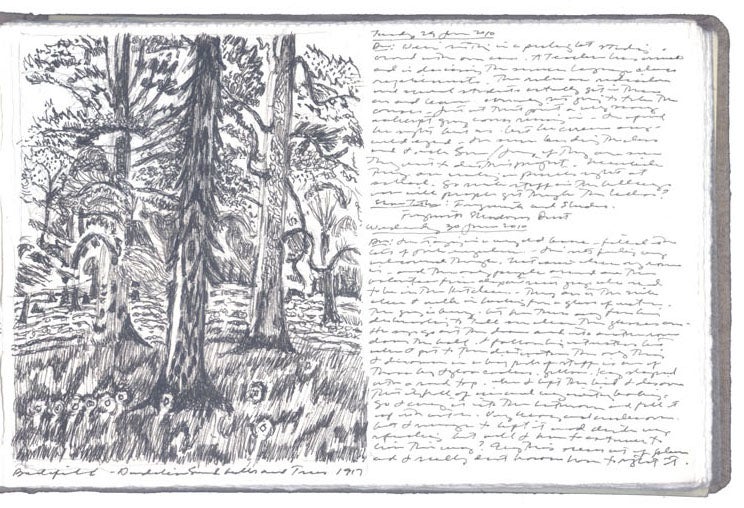

Charles Ritchie sketch after a watercolor by Charles Burchfield, Book 134, 2010, page size:4 x 6', pen and ink on Arches paper.